Today’s guest post is from Jon Martin, a seasoned investigative journalist focused on semiconductors, consumer technology, and emerging trends. Jon has over a decade of experience, including a lucrative stint as a lead writer and host for Linus Media Group. Jon holds a Juris Doctor from Boston College Law School, and is currently pursuing new career opportunities.

The CHIPS and Science Act, signed into law in 2022, was an attempt by the United States federal government to enhance the nation’s ability to manufacture semiconductors and conduct relevant research. In addition to tax breaks, the Act calls for $39 billion in federal subsidies to be given to companies to produce more chips inside the US, as well as another $11 billion for advanced R&D.1

Over two years later, the money promised to chip firms is making its way out of the government’s coffers. Today, we’ll take a look at exactly where that money is going and the impacts we can expect.

The format of this article will cover the following topics:

-

The Origin of the CHIPS Act

-

Leading Logic Foundry: Intel, TSMC, Samsung

-

Memory Foundry: Micron, Samsung, SKHynix

-

Essential: GlobalFoundries, Texas Instruments, Wolfspeed, NSTC

-

Best of the Rest

-

International Response

-

Current State of Play with the new Administration (as of March 2025)

ORIGINS OF THE CHIPS ACT

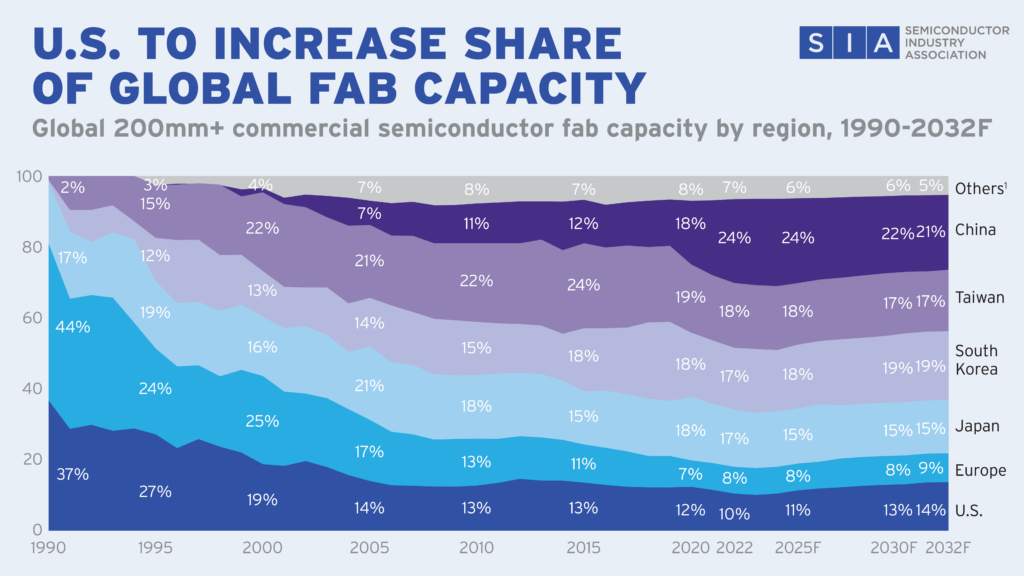

In 1990, the overwhelming majority of chip manufacturing was taking place in the US, Japan, and various European countries. The US alone counted for roughly 40 percent of global semiconductor production, but with the rise of China, Taiwan, and South Korea as new chipmaking powers, America’s share of the global bag of chips has dwindled to approximately 10-14 percent in recent years.2

Even though the world’s advanced economies are largely considered post-industrial, chipmaking is an area where domestic manufacturing is now being treated as a high priority for economic and national security reasons. The infamous COVID-era chip shortage was partly a result of the disruption of supply chains, which was made more pronounced by the logistical headaches and increased costs associated with shipping chips abroad, as well as the US-China trade conflict that hampered the ability of Chinese firms to export chips to the American market.

Of course, a pandemic that resulted in widespread lockdowns and the subsequent rise of remote work only exacerbated the problem; even though stay-at-home orders are now a memory, a 2023 study indicated that remote work remains nearly ten times more common today than it was before COVID struck.3

Aside from the supply-and-demand lessons of COVID, the US government has been concerned about the national security implications of importing so many chips into the country. The obvious concern is over the Chinese government pressuring its domestic chipmakers into incorporating backdoors to enable espionage or cyberattacks, but the argument for made-in-America chips doesn’t completely rest upon such skullduggery actually happening.

There are also worries that China could choke off the chip supply to the US and her allies to gain economic leverage, especially in a time of conflict, and that Chinese firms that produce large quantities of chips on older nodes – which are still widely used in embedded applications. This could potentially take legacy-chip revenue away from chipmakers in other countries, including the US, preventing them from re-investing that money into leading-edge products.

Even with Taiwan, a longtime US ally, hosting TSMC, there is also concern about what would become of such a key supplier of chips to Western and allied nations if China were ever to initiate a war against Taiwan. China’s refusal to rule out the use of military force to make Taiwan part of the PRC is both long-standing and well-documented, and while a conflict appears unlikely in the short term, the rhetoric out of Beijing has done little to convince the West that TSMC can be relied upon indefinitely.

As polarized as the US political scene has been and still is, these concerns were enough to give the CHIPS Act some measure of bipartisan support. Although nearly all Senate Democrats voted in favor of the bill, roughly one-third of the chamber’s Republicans joined them4; in the House, 24 Republicans also broke ranks with their party to vote in favor of the bill’s final version.5 Opposition to the bill, which ironically had both protectionist and free-market themes, as well as accusations that the program would be another undesirable instance of “corporate welfare,” ultimately could not stop it from becoming law.

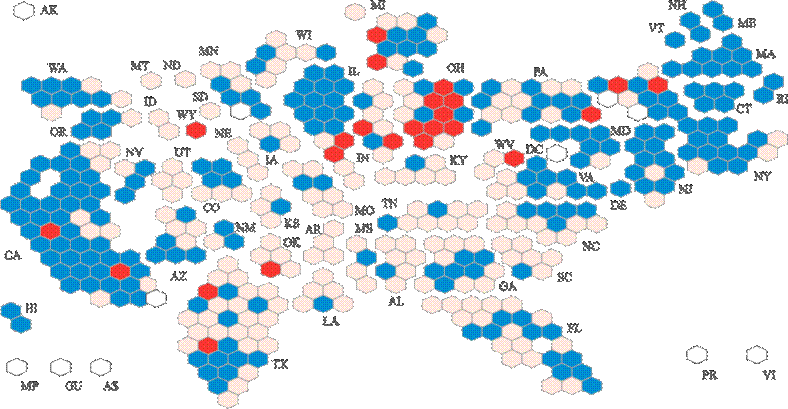

Each shaded hexagon represents a “yes” vote in the House. Democrats are in blue, Republicans are in red.

However, one particular concern raised by opponents – a lack of guarantees that CHIPS Act money would indeed be spent domestically – was partly addressed by the Department of Commerce after the bill’s passage. The department published a rule in 2023 that prohibits CHIPS Act beneficiaries from investing in chip manufacturing in a “foreign country of concern” for ten years after receiving the monetary award – a label that, unsurprisingly, applies to China as well as to Russia. The rule also prohibits recipients of CHIPS Act benefits from using the funds to build or modify a manufacturing facility anywhere outside of the US.6 With Asia being a significantly less expensive location to build and operate fabs, the federal government is hoping that the CHIPS Act will end up being a valuable carrot-on-a-stick.

BLUE CHIPS:

Proponents of the CHIPS Act have targeted relatively lofty numbers as being indicative of adequate investment into the domestic chipmaking industry. Then President Biden wanted 20 percent of leading-edge chips to be American-made by 2030.7 Then-Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger stated in a 2021 interview that he wanted 30 percent of the globe’s chip supply to come from the US, which he referred to as a “moonshot.”8

Intel is currently the single largest beneficiary of CHIPS Act funds, with the company receiving an award of up to $7.86 billion in November 2024 intended for fabs in Arizona, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon. The award will additionally include up to $25 billion in tax credits; Intel can max out this amount by investing $100 billion in these fabs.9 Although the award was originally for $8.5 billion, it was reduced as the company had also received a hefty $3 billion defense contract for military semiconductors.10

Intel has a number of pre-existing facilities in the US, but the Ohio site, which will play host to a pair of brand-new foundries, is emblematic of the crossroads Intel finds itself at.

Although Intel has not made any statements to this effect, there has been speculation that the company is considering spinning off part of its foundry business as a cost-cutting measure – a partial IPO similar to its subsidiaries Mobileye and Altera. While it’s intuitive that factories pumping out large quantities of extremely sophisticated microchips are expensive to build and operate, what might be less obvious is exactly why Intel has had difficulties spinning off manufacturing – assuming, of course, that this is indeed something they want to do.

The primary difficulty in a spin-off is that Intel’s foundries have been notoriously siloed off from outside chip designers. Unlike a dedicated contract manufacturer such as TSMC or GlobalFoundries, Intel fabs have not used industry-standard EDA software that allows third parties to design chips that can be manufactured on Intel’s equipment. While this changes with Intel’s newest technology, the bulk of its foundry facilities for 14/10/7 nm process nodes still use Intel-internal only software tools for chip design. This means, externally, those facilities have no value in contract manufacturing at this time.

In early 2024, Intel announced a partnership with Taiwanese chipmaker UMC to design a ‘12nm’ toolkit to alleviate this issue and allow Intel to act as a contract manufacturer, using its traditional Intel 14/10/7 foundry production.11 This would seem to enable Intel to part-IPO its foundry business, and indeed, there is speculation that Intel has been planning to spin off the new Ohio facilities that are still currently under construction.

However, even though the CHIPS Act is providing funds for Intel’s Ohio project, the Act is also ironically an obstacle to any plan Intel may have to do this. Intel’s agreement with the US government imposes restrictions on how much of a new foundry business Intel would be allowed to divest.12 Exactly how much would depend on whether the new entity is publicly traded, but in any case, Intel would have to maintain a controlling stake, or risk losing money from the CHIPS Act.

Then, of course, there’s the wrinkle that Gelsinger, who pushed Intel to modernize its manufacturing capabilities, recently stepped down as the company’s CEO in December 2024. It remains an open question as to whether the new regime under new CEO Lip-Bu Tan wants to commit to continue operating fabs over the long term, or if they want to steer Intel toward a product-focused fabless model similar to rivals AMD and Nvidia; interim chair Frank Yeary’s recent comments about prioritizing product has fueled speculation about Intel’s path forward.

Attempting to entirely divest itself of its foundry business would certainly mean forfeiting funds from the CHIPS Act – but the bigger blow would be to the US government, as there are no other domestic chipmakers currently capable of producing leading-edge silicon at scale. The concerns here for Washington would go beyond the purely economic, as Intel was also awarded $3 billion for a project dubbed the “Secure Enclave.” Not to be confused with Apple’s hardware-based encryption solution, Intel’s Secure Enclave is a to-be-constructed facility for the secure manufacture of chips for the American military.13

While it’s unlikely Intel would be able to pull off such a massive pivot in time for its next-gen 18A chips, it isn’t out of the question that the company may ultimately decide washing its hands of its expensive manufacturing facilities is worth giving up federal subsidies.

TSMC, MEET TEAM USA

The second-largest beneficiary of CHIPS Act funds isn’t even an American company; it’s none other than TSMC, which is receiving up to $6.6 billion from the program. TSMC will also have access to another $5 billion in loans.14

Although the US government views Intel as critical to its efforts to get closer to technological sovereignty, having an expanded TSMC presence on American soil may be just as important, as the Taiwanese concern currently manufactures around 90 percent of the world’s leading-edge (7nm and below) chips.15

TSMC has had a facility in Washington state since 1996 operating under its WaferTech brand, but that facility only manufactures chips on the 160 nanometer and larger nodes.16 Most of TSMC’s leading-edge production is in Taiwan itself, but the CHIPS Act is intended to help TSMC to build comparable foundries in the US, the first of which is a fab in Phoenix that’s expected to churn through around 20,000 wafers each month.17

This fab has been in the works since 2020, but has run into delays due to significantly higher costs, difficulty finding qualified workers, and complex legal and bureaucratic requirements. However, the facility is now on track for full production at the 4-nanometer node during the first half of 2025, and is already producing A16 SoCs for Apple – possibly for the new iPhone SE or iPad.18

TSMC initially announced investing over $65 billion in its Arizona site overall, as the company is planning to build two more fabs: one for two- and three-nanometer chips, with production scheduled to begin in 2028; and one for two-nanometer or smaller processes, slated to begin production by the end of 2030.19 In Q1 of 2025, TSMC held a conference at the new site announcing another $100 billion of investment in the USA, including new facilities and an R&D center, although no timescale was put on this investment. Crucially, no word comes in the form of construction of packaging facilities, a key part of TSMC’s IP, which today is solely provided in Taiwan.

In addition to direct subsidization of construction costs, TSMC is planning to use a portion of the CHIPS Act award to solve its labor issues. Roughly half of the current workforce at the Arizona site is composed of temporary workers from Taiwan – at least partly a result of American workers not having the same expertise as their Taiwanese counterparts, but there have also been allegations that the facility is falling well short of US workplace safety standards.20

With further allegations of bias against local workers in favor of the Taiwanese visa holders and reports that TSMC wants to use American engineering graduates as technicians – resulting in some of them seeking higher-level jobs elsewhere – TSMC has made several commitments to the federal government in order to receive CHIPS Act funds, including supporting local apprenticeship programs, partnerships with engineering departments at several major American universities, and confirming that labor laws are being followed. With the company claiming that 6,000 local jobs will be created21, TSMC is desperate to hire and retain US nationals, especially as “a mismatch and loss of worker skills in the…operation of manufacturing facilities” is a domestic issue the Department of Commerce specifically hopes to address with the CHIPS Act.22

ECONOMICS FOR SAMSUNG

The other non-American firm to be receiving a huge chunk of CHIPS Act funds is Samsung. Their award of up to $4.745 billion is primarily intended for a facility in Taylor, Texas23 – just outside of Austin – that broke ground in 2022 and was originally scheduled to come online in 2024 for mass production.

However, this award was recently reduced from an initial $6.4 billion, and while the reasons for this aren’t fully clear, it may be tied to Samsung’s problems with yields on smaller process nodes. Although the Department of Commerce hasn’t given details on conditions attached to Samsung’s CHIPS Act award, funding of all awards is contingent upon the recipient’s ability to hit certain milestones with their foundry projects.

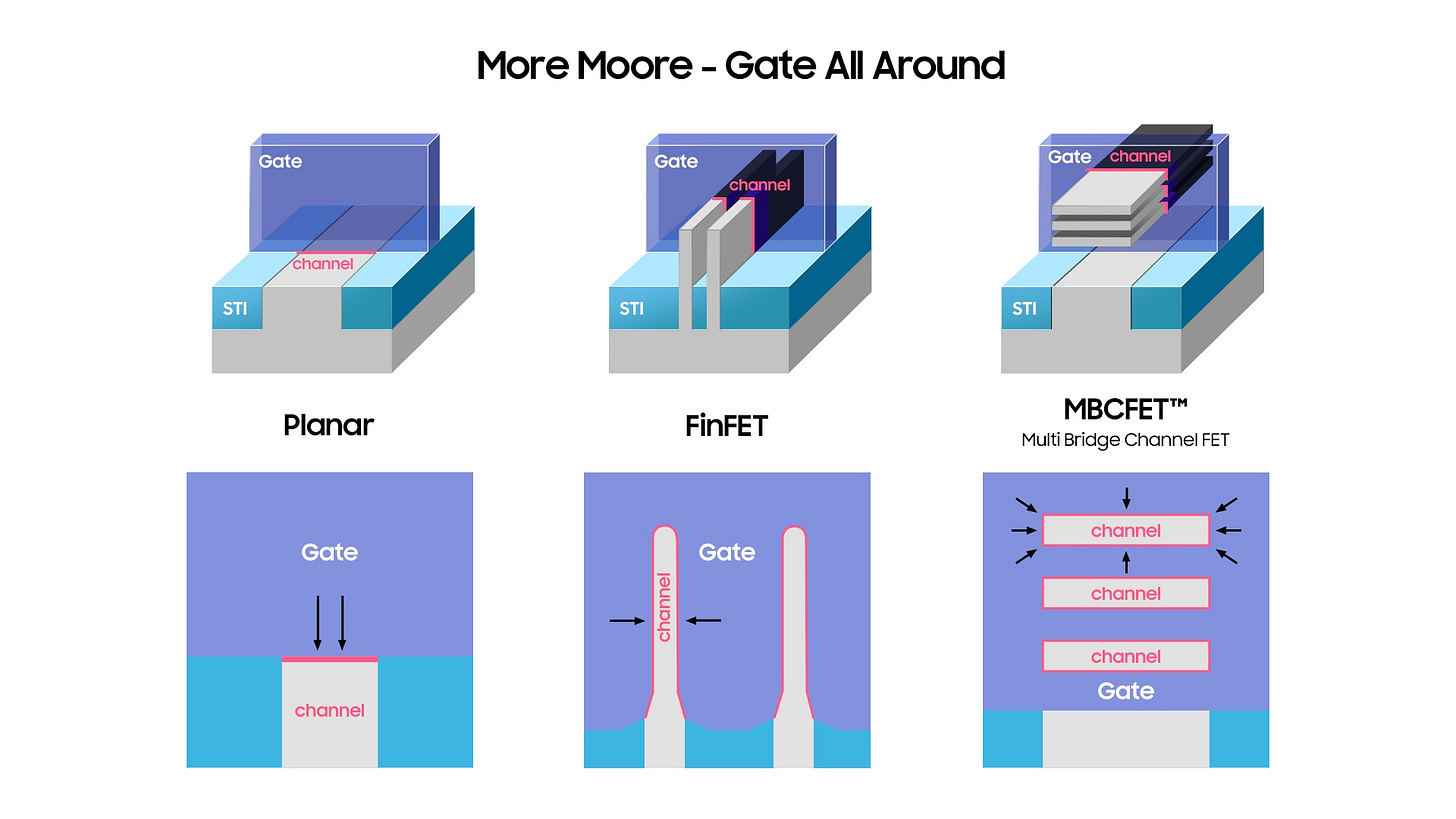

The Taylor site is intended to make chips at the 4-nanometer node and below, but yield issues have reared their ugly heads at Samsung’s other facilities, with a report from Business Korea indicating that the company is struggling with both 2- and 3- nanometer production.24

This appears to have forced Samsung to push volume production at the Taylor site back to 2026 – with a second fab at the same site now due to come online in 2027 – with yields for gate-all-around transistors reportedly below 20 percent.25 Given the delay in volume production, Samsung has also slashed its workforce at the site, with only a skeleton crew currently manning the works in Taylor.26

A report in October 2024 indicated that there was also a delay in Samsung taking deliveries of EUV machines from ASML – still the world’s only manufacturer that makes the EUV equipment necessary for next-gen chips – as Samsung had not yet secured enough customers to finalize the purchase of the machines which carry a price tag of approximately $150-200 million each. Orders for other kinds of equipment were similarly delayed.27

IT’S ALSO A MEMORY GAME:

The companies we’ve discussed up until this point received CHIPS Act funding primarily for producing advanced logic chips, but that doesn’t mean that memory was forgotten (pun intended) on Capitol Hill. Micron’s grant of $6.1 billion makes them the only other private company to receive a multi-billion dollar check from the federal government.28

The grant is intended for two sites: one in Clay, New York, which is just outside of Syracuse; and one in Boise, Idaho. The lion’s share of the money – $4.6 billion – is earmarked for the Clay site, as the plan is to build two brand-new fabs – and eventually have a total of four – for leading-edge DRAM and HBM. In Boise, Micron is adding to an existing leading-edge R&D site with a fab of similar size to one of the New York fabs.29

Additionally, Micron is receiving an extra $275 million from the CHIPS Act to expand its plant in Manassas, Virginia – just outside of Washington, DC – to bolster its total investment of up to $2.17 billion at the site.30 Total Micron investments in US chip production are planned to be around $50 billion through 2030.31

Although memory doesn’t get the same headlines as logic chips, leading-edge memory is quickly becoming a crucial piece of the AI race. The amount of data that passes through AI servers both for training models and for generative purposes means that both capacity and bandwidth demands on memory are a key consideration.

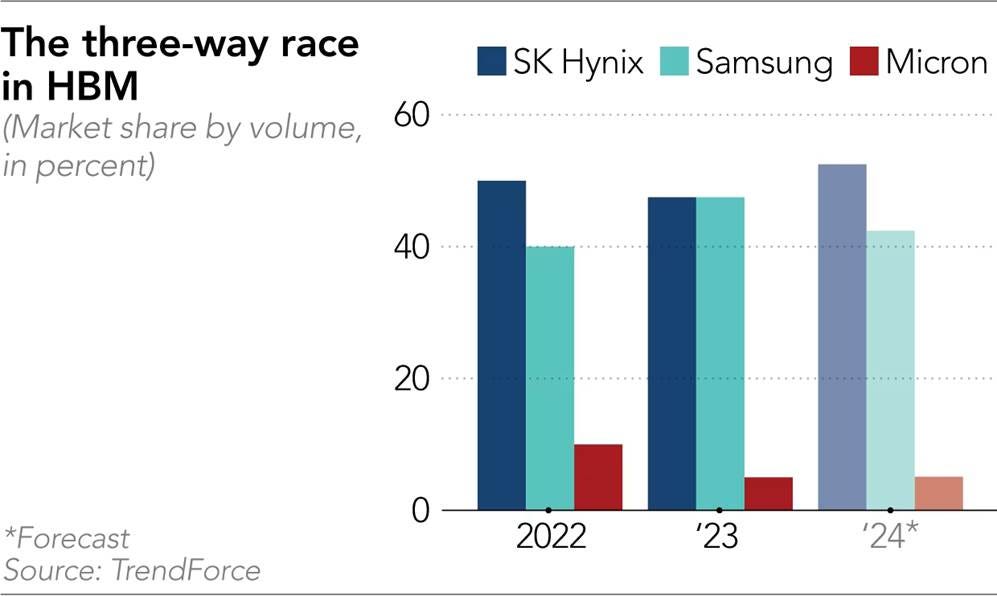

HBM (high-bandwidth memory) commonly used in higher-end AI hardware deployments is a key area where Micron would like to catch up to other memory market leaders like SK Hynix and Samsung. The two Korean giants take up a whopping 90 percent or so of market share in the HBM space, with Micron taking up the remainder.32

Although South Korea, like Taiwan, is an important strategic ally for the West, Micron’s status as the only memory manufacturer based in America made it a very attractive candidate for CHIPS Act funding, which may help the company become more competitive against the Koreans.

Micron’s struggles have come not from problems with manufacturing, but from being late to the HBM game. Although Micron controls a healthier one-fifth to one-fourth of the overall DRAM market, the company did not start working on HBM production until 2018, several years after SK Hynix. Micron also made the decision not to produce HBM3 – common in current-gen AI deployments – and instead focus on a newer revision of the technology, HBM3e. HBM3e as a technology is initially being used in Nvidia’s new Blackwell products for datacenters, and AMD’s latest generation MI300X and MI325X accelerators. However, at this time, we believe only SK Hynix has the contract for Nvidia while AMD is multi-sourcing from SK and Micron.33

Micron is bullish on its ability to catch up quickly in the HBM market; the company believes it can reach parity with its share of the DRAM market before the end of 2025, especially as Micron is already sold out of HBM through the end of the calendar year.

There is little doubt that Micron expects the demand for leading-edge memory to continue thanks to AI. The new fab in Boise is expected to be completed in late 2025 with memory production starting early next year, while the fabs in New York are expected to break ground in November 2025 to allow authorities to assess environmental impacts. Expansion of the Manassas site should be taking place over the next few years, which is to include Micron’s 1-Alpha process; although Micron has since developed newer processes, 1-Alpha is expected to allow the Manassas site to “significantly” increase its wafer output.34

BIGGER IN TEXAS?

Texas Instruments didn’t receive the eye-watering sums that the previously-mentioned companies did, but they still received up to a healthy $1.6 billion to support the construction of three new fabs. Unsurprisingly, two of these will be in none other than the state of Texas, with the third in Utah.35

Unlike names more well-known to folks in the PC enthusiast scene, Texas Instruments doesn’t focus on leading-edge silicon. Instead, TI produces embedded chips that do not require the latest process nodes to manufacture. In fact, TI uses nodes that might seem downright ancient – think 40 nanometers to 130 nanometers.36 For reference, the 130 nm process was being used in then-current desktop CPUs all the way back in 2001.

However, the overwhelming majority of products still need chips based on these processes for applications other than higher-end logic. Many of these chips are used in cars, appliances, and peripherals; some of these are analog processors, which serve as a link between some environmental variable and a digital processor. Temperature sensors, power controllers, and analog/digital converters in audio equipment are all examples of common products that roll out of TI’s fabs. For reference, a modern smartphone is often only 30% leading edge, while the other 70% of silicon is made on legacy nodes such as these.

The relatively large CHIPS Act grant awarded to TI is a reflection of the fact that the US isn’t just concerned about securing a reliable supply of leading-edge silicon; there’s also a concern over other chips necessary for modern electronics. During the pandemic, the well-publicized chip shortage was partly caused by supply chain issues with analog chips and other chips built on legacy nodes; cars, for example, aren’t using top-end Ryzen 9 or Core 9 CPUs to power their infotainment systems, but shortages of the types of less-powerful chips produced by TI led, in turn, to a smaller inventory of cars and other common products, not to mention actual PCs and phones.

Additionally, the ICs built by companies like TI tend to come in matched sets: a term of art in the industry that indicates a specific bundle of ICs that are needed to assemble a particular product. This puts additional pressure on chipmakers to have adequate capacity to meet demand.

The CHIPS Act grant will be part of a total investment of over $18 billion that TI is planning to pour into its manufacturing operations through 2029, with their CEO stating that they’re expecting to nearly double manufacturing capacity by 2030.37

HEY, LOOK WHAT I FOUNDRY’D

The final company to score over a billion dollars in CHIPS Act grants is GlobalFoundries – the company that used to comprise of AMD’s fab division before it was spun off in 2009. Although GlobalFoundries has maintained a relationship with AMD for a number of products, GloFo has since gotten out of the leading-edge business. Similarly to Texas Instruments, GlobalFoundries now focuses on nodes for embedded chips, which they dub ‘essential nodes’; the company currently manufactures products on the 12-nanometer node and higher.

GloFo’s award is for up to $1.5 billion, and will support the construction of a brand-new fab in Malta, New York (north of Albany), which will focus on chips for data center AI, aerospace, defense, and the automotive industry. The money will also go toward expanding an existing fab at the same site, again mostly to go into domestically-produced motor vehicles.

Aside from the New York site, the award will also go toward upgrading another existing fab in Essex Junction, Vermont (outside of Burlington), to mass-produce gallium nitride semiconductors. Gallium nitride is well-known for giving us smaller chargers for phones and laptops thanks to smaller transistor sizes and better efficiency; indeed, it appears that the Vermont site will indeed be producing chips that aid in power delivery.38

Over the next decade, GloFo is planning to invest over $12 billion into the two sites.39 Ironically, the company was recently in hot water with the federal government due to shipping products to a blacklisted Chinese semiconductor manufacturing firm, resulting in having to cough up a $500,000 fine40 – so it appears that the DoC still believes GloFo will have no problem playing by the rules of a program designed to keep chips out of the hands of US adversaries.

THE OF TOBACCO ROAD

Another massive CHIPS Act grant went to a company you may not have heard of. Wolfspeed, of Durham, North Carolina, was awarded $750 million in an effort to advance domestic development of chips for electric vehicles.41

Wolfspeed specializes in the production of silicon carbide chips, which, like gallium nitride, is emerging as an alternative to silicon in applications that demand high power levels – such as EV batteries and powertrains. For example, Tesla uses silicon carbide inverters to convert DC to AC, which powers their electric motors. Wolfspeed is also looking to supply more SiC chips for the renewable energy industry, AI datacenter deployments, and other industrial power applications.

SiC has actually been around for over a century as a semiconductor, but the need for more power-efficient materials for applications like EVs has renewed interest in it – SiC-based products have historically been notoriously difficult to manufacture.

Wolfspeed has certainly not been immune to this – the company has not turned a profit in roughly a decade, and has been hampered by shortages of silicon carbide wafers. A slump in demand for electric vehicles also has not helped matters. Wolfspeed stock, which hit a high of approximately $140 in November 2021, was trading for below $5 per share in mid-January.42

The CHIPS Act funding should provide the company with some much-needed help; the money will be going to a new two-million square foot facility in Siler City, NC, southeast of Greensboro, as well as to an expansion of an existing facility in Marcy, NY, just outside of Utica. Unsurprisingly, given the company’s shaky finances, the DoC agreement requires Wolfspeed to “take additional steps to strengthen its balance sheet.” The North Carolina and New York projects are part of an expansion plan that is project to cost around $6 billion; production in Siler City is scheduled to begin this year with a completion date of 2030.43

Meanwhile, Wolfspeed plans to close its existing fab in Durham, which operates on a more costly process 150 nm node, with an eye toward shifting production to the Marcy site, though the company will still maintain its headquarters and other facilities in the Bull City. The new site in North Carolina will supply the New York site with the 200 mm wafers Wolfspeed needs to execute its new manufacturing strategy.44

SAYING HYNIX TO THE CASH

South Korean memory concern SK Hynix initially seemed rather unenthusiastic about the CHIPS Act, as their vice-chair opined in 2023 that the application process was “too demanding.” Specifically, the South Korean government took issue with Washington’s requests for detailed information about both applicants’ technologies and financials45; but unsurprisingly, it would take a lot for a company to turn down free money, and SK Hynix did indeed apply for CHIPS Act funding, earning an award of up to $458 million.

Similarly to Micron, SK Hynix is intending to use this money to focus on the production of HBM – specifically HBM4 and/or 4e – mainly for use in AI applications. This will entail a new facility in West Lafayette, Indiana, on the campus of Purdue University, a school which focuses on applied sciences. Overall investment at the site is expected to total $3.87 billion, with mass production expected to start in late 2028.46

NSTC (not NTSC)

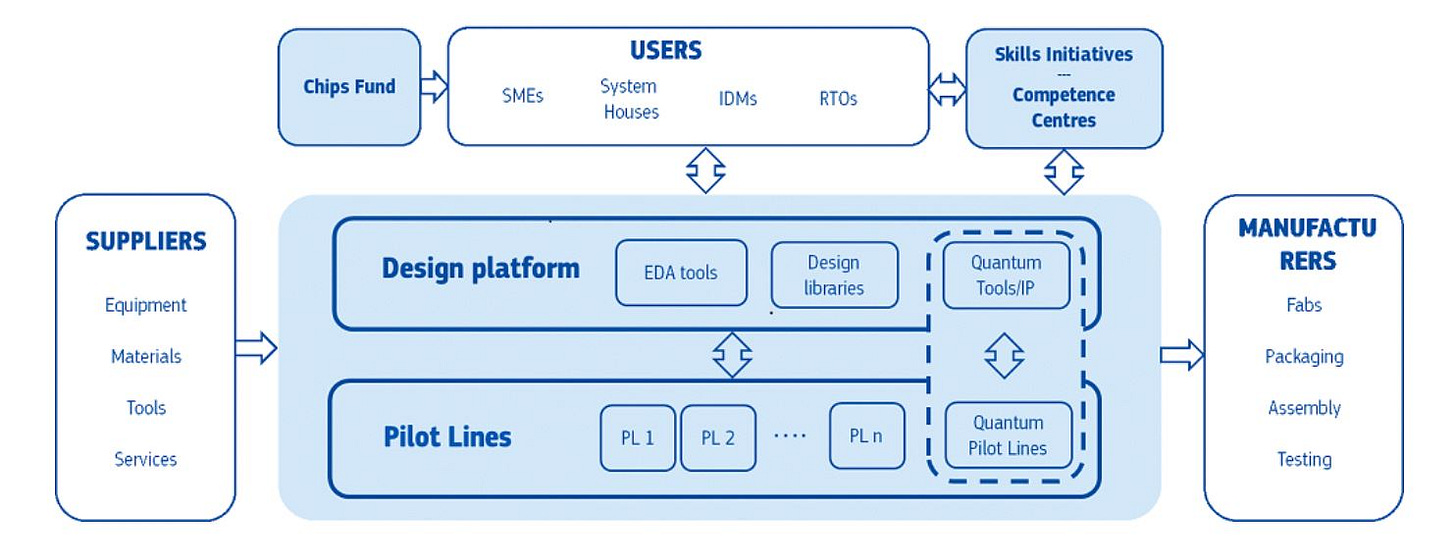

The US government has also reserved a piece of the CHIPS Act pie for itself, as up to $6.3 billion was given to Natcast, which is a hybrid public-private entity established by the CHIPS Act specifically to run the National Semiconductor Technology Center (NSTC). Unlike many of the other CHIPS Act award recipients, the NSTC is focused on R&D rather than large-scale chip production.

The NSTC’s flagship location will be located in Sunnyvale, California – also home of AMD’s headquarters – and will focus on research into design automation, security, and chip design, with a major goal being to provide companies with tools and processes to help them design chips more quickly and at lower cost.47

Meanwhile, another site in Albany, New York – which will be within the existing Albany NanoTech complex – will focus on EUV lithography, with one goal being to allow access to high-NA EUV technology by 2026. (The site already has one conventional EUV machine in place.)48 This site is a public-private partnership between IBM, the state of New York, and SUNY.

Ian’s video channel has an episode on the development of the site in Albany and the importance of the NSTC there.

A third site, located in Tempe, Arizona on the campus of Arizona State University, will host a packaging facility. Rather than being designed for full-scale production, this facility will instead allow for the testing of new devices and packaging technologies that aren’t yet ready for introduction into the marketplace.49

BEST OF THE REST

The CHIPS Act grants we haven’t discussed yet are for significantly smaller amounts to around two dozen companies. The aims some of these awards are fairly similar to those of the larger grants. Bosch, which you might know more for their line of home appliances, is getting $225 million for silicon carbide manufacturing to supplement Wolfspeed’s efforts. Meanwhile, the aptly-named Analog Devices is receiving $105 million to manufacture sensors – similar to the Texas Instruments grant, but with a focus on defense, space, and other commercial applications.

However, other grants are aimed at more niche manufacturing that is still nonetheless important to the overall American technology sector:50

Akash Systems is getting up to $18.2 million for a facility that will focus on using synthetic diamonds in heat sinks for various high-performance ICs.

Coherent ($COHR) is receiving up to $112 million for indium phosphide-based optoelectronics, used for high-speed connections in medical devices, smart cars, and AI datacenters.

Corning ($GLW), better known in the consumer tech world for the Gorilla Glass commonly used in smartphones, is the beneficiary of up to $32 million for glass used in photomasks and mirrors inside EUV machines.

Edwards Vacuum is getting up to $18 million to make vacuum pumps that remove the toxic gases produced in the semiconductor manufacturing process.

Rocket Lab is receiving up to $23.9 million to manufacture solar cells for rockets and satellites.

An R&D consortium headed by the previously-mentioned Albany NanoTech is receiving up to $40 million for a regional hub dedicated to workforce development for chipmaking.

Sumika was allocated up to $52.1 million for chemical production, especially high-purity isopropanol. Unlike the isopropanol that is also labeled as rubbing alcohol at pharmacies, the semiconductor grade isopropanol used in chip manufacturing has to be ultra-pure: think 99.9% and greater purity for applications like rinsing and drying wafers.

These additional, smaller grants track with the DoC’s goal of not just competing more effectively against foreign chipmaking operations, but also of trying to secure as much of the manufacturing and supply chain as possible.

INTERNATIONAL RECEIPTS

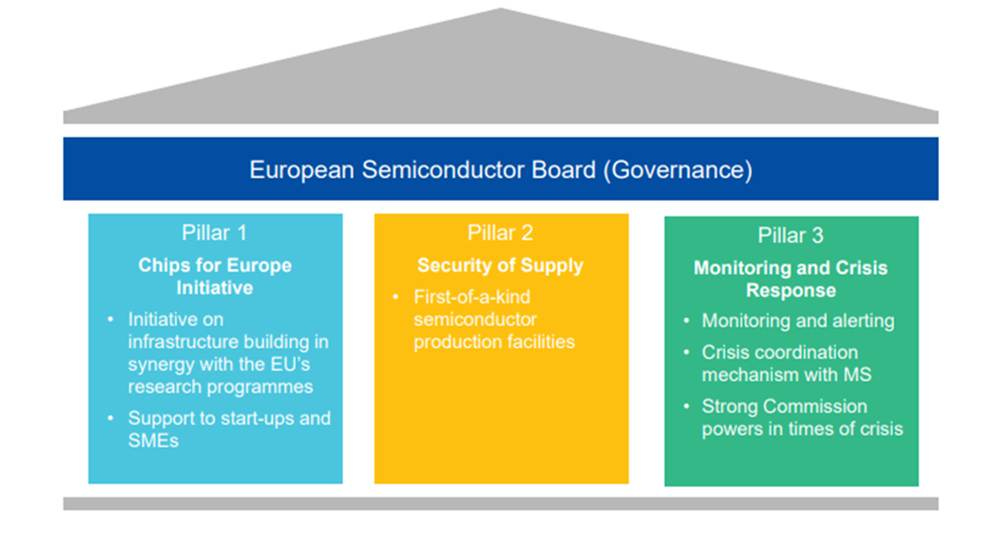

The US, of course, is far from the only country wanting to reduce its dependence on foreign chips. The European Union has passed its own Chips Act (yes, the name is actually the same minus “CHIPS” being an acronym) which is worth $47 billion (€43 billion) and is explicitly focused on making the EU self-sufficient in the event of a major supply disruption, as well as getting the EU to 20% of overall global chip market share – the same percentage the US is aiming for in its CHIPS Act. The investment strategy is similar to the American one as well, with the money focusing on manufacturing facilities, skill development, and tools for product design.51

Meanwhile in Taiwan, their government has amended the Statute for Industrial Innovation to provide for a 25% tax break for R&D investments, with an additional 5% on purchasing equipment for advanced chip fabrication. Although TSMC, which has a long-running relationship with the Taiwanese government, will be a major benefactor, other companies like MediaTek, Realtek, Delta Electronics, and Phison also stand to benefit.52

South Korea has passed similar tax incentives; investments in semiconductor manufacturing and other technologies deemed strategic will result in up to a 35 percent tax break for small- and medium-sized companies, while larger businesses can get up to a 25 percent credit. Total savings for 2024 were projected to be nearly $3 billion53, but South Korea also passed another $19 billion in support for its domestic chipmakers, including Samsung and SK Hynix. The country’s stated goal, at least for logic chips, is to get its global market share up to 10% from the 2% at which it currently sits.54

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

With Trump’s second administration taking over, concerns have been raised over whether the CHIPS Act will be implemented as planned. Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson, a Trump ally, stated in early November that the GOP would “probably” try to repeal the CHIPS Act, only to quickly walk back the statement. Another Republican, Brandon Williams, claimed that Johnson misheard the question he was asked about the Act.55 (Williams was later named as Trump’s pick to serve as Under Secretary of Energy for Nuclear Security.)

However, given that Johnson later claimed that the bill should be “streamlined” to “eliminate its costly regulations,”56 there has still been some concern that the incoming administration may not treat disbursement of CHIPS Act funds as a particularly high priority, especially with Trump himself expressing dislike at the idea of subsidizing chipmakers, instead favoring an approach that involves charging tariffs on foreign-made chips to encourage companies to relocate manufacturing facilities to the US.57

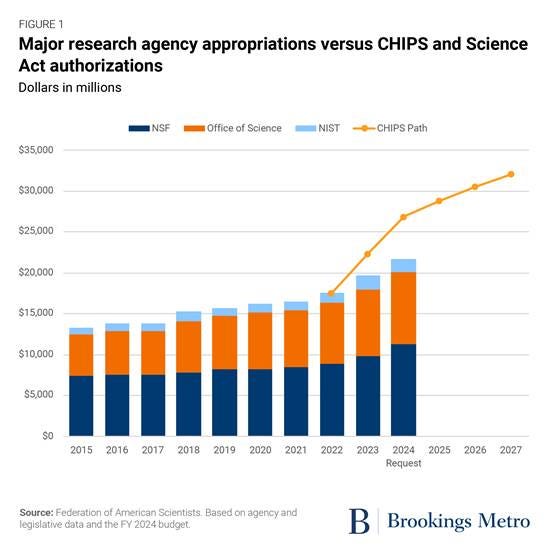

However, do proponents of the Act have to worry about the program being significantly crippled? Howard Lutnick, Trump’s pick to lead the Department of Commerce, has publicly committed to the CHIPS Act.58 On top of that, 85 percent of the allocated grant money has already been assigned in binding contracts between the federal government and the private beneficiaries. The Trump administration cannot unilaterally decide to simply not award the money.59

How CHIPS Act awards stack up next to funding of federal research agencies.

That does not mean, of course, that aren’t still wrinkles. Actual disbursement of the funds depends on companies hitting certain milestones, meaning that funds to be awarded later could become a point of contention if beneficiary firms violate a minor contractual term, for example.

Vivek Ramaswamy, Republican presidential candidate that was initially tapped to lead the unofficial, Elon Musk-backed “Department of Government Efficiency,” has called the CHIPS Act monetary awards “wasteful subsidies” and “11th-hour gambits” that “DOGE” will be reviewing, with the latter comment referring to the Biden administration’s push to finalize CHIPS Act deals before the expiration of Biden’s term.60 (Ramaswamy ultimately left “DOGE” around the time Trump took office.)

However, there does not appear to be an appetite on Capitol Hill to change the heart of the CHIPS Act, though its labor and environmental provisions – common targets for Republicans – may be revisited at some point.

Although corporate subsidies have faced heavy criticism over the years from both the left and the right, it does appear that the weaknesses around the tariff approach may have convinced enough people in Washington that the CHIPS Act should remain law. Aside from the general fear that companies hit by tariffs will pass the additional costs on to consumers, chipmaking specifically is a capital- and resource-intensive industry in which tariffs may not be enough to lure foreign chipmakers to the US. Of course, chipmaking is far from the only industry to have high startup and operational costs, but given the critical economic and strategic importance of semiconductor manufacturing, the CHIPS Act seems to be palatable enough to America’s powers-that-be, even among a healthy number of Trump’s allies. Indeed, the European Union has taken a similar approach with the European Chips Act, which, as previously mentioned, also provides subsidies rather than relying on tariffs.

If the US can overcome its shortage of the skilled labor needed for chipmaking – a problem the Act aims to address at least partially – the law will likely go a long way toward meeting its goal of improving American supply chains, national security, and overall economic standing. Whether the country will be able to significantly reduce chip imports, or whether it will hit Biden’s specific goal of making 20 percent of leading-edge chips by the end of the decade, are more open questions.

Update on Tariffs:

Based on the Tariffs announced by the current administration, it would appear that while semiconductors might not be implicated, anything built with semiconductors or include semiconductors inside are going to be under tariffs. Not only that, but manufacturing machines for semiconductors with components from outside the USA (so, all of them) will fall under the tariffs, meaning that any USA fab buildout or expansion is going to have additional costs to it. We’ll keep tabs on this as-and-when official statements are released.